Dear friends,

Some people today are discouraging others from learning programming on the grounds AI will automate it. This advice will be seen as some of the worst career advice ever given. I disagree with the Turing Award and Nobel prize winner who wrote, “It is far more likely that the programming occupation will become extinct [...] than that it will become all-powerful. More and more, computers will program themselves.” Statements discouraging people from learning to code are harmful!

In the 1960s, when programming moved from punchcards (where a programmer had to laboriously make holes in physical cards to write code character by character) to keyboards with terminals, programming became easier. And that made it a better time than before to begin programming. Yet it was in this era that Nobel laureate Herb Simon wrote the words quoted in the first paragraph. Today’s arguments not to learn to code continue to echo his comment.

As coding becomes easier, more people should code, not fewer!

Over the past few decades, as programming has moved from assembly language to higher-level languages like C, from desktop to cloud, from raw text editors to IDEs to AI assisted coding where sometimes one barely even looks at the generated code (which some coders recently started to call vibe coding), it is getting easier with each step. (By the way, to learn more about AI assisted coding, check out our video-only short course, “Build Apps with Windsurf’s AI Coding Agents.”)

I wrote previously that I see tech-savvy people coordinating AI tools to move toward being 10x professionals — individuals who have 10 times the impact of the average person in their field. I am increasingly convinced that the best way for many people to accomplish this is not to be just consumers of AI applications, but to learn enough coding to use AI-assisted coding tools effectively.

One question I’m asked most often is what someone should do who is worried about job displacement by AI. My answer is: Learn about AI and take control of it, because one of the most important skills in the future will be the ability to tell a computer exactly what you want, so it can do that for you. Coding (or getting AI to code for you) is the best way to do that.

When I was working on the course Generative AI for Everyone and needed to generate AI artwork for the background images, I worked with a collaborator who had studied art history and knew the language of art. He prompted Midjourney with terminology based on the historical style, palette, artist inspiration and so on — using the language of art — to get the result he wanted. I didn’t know this language, and my paltry attempts at prompting could not deliver as effective a result.

Similarly, scientists, analysts, marketers, recruiters, and people of a wide range of professions who understand the language of software through their knowledge of coding can tell an LLM or an AI-enabled IDE what they want much more precisely, and get much better results. As these tools continue to make coding easier, this is the best time yet to learn to code, to learn the language of software, and learn to make computers do exactly what you want them to do.

Keep building!

Andrew

A MESSAGE FROM DEEPLEARNING.AI

Pre-enroll now for the new Data Analytics Professional Certificate! Gain job-ready skills in data analysis, whether you’re starting a career as a data analyst or enhancing your ability to prepare, analyze, and visualize data in your current role. This program covers both classical statistical techniques and emerging AI-assisted workflows to help you work smarter with data. Learn more and sign up

News

Compact Reasoning

Most models that have learned to reason via reinforcement learning were huge models. A much smaller model now competes with them.

What’s new: Alibaba introduced QwQ-32B, a large language model that rivals the reasoning prowess of DeepSeek-R1 despite its relatively modest size.

- Input/output: Text in (up to 131,072 tokens), text out

- Architecture: Transformer, 32.5 billion total parameter

- Performance: Outperforms OpenAI o1-mini and DeepSeek-R1 on some bencharks

- Features: Chain-of-thought reasoning, function calling, multilingual in 29 languages

- Undisclosed: Output size, training data

- Availability/price: Free via Qwen Chat. Weights are free to download for noncommercial and commercial uses under an Apache 2.0 license.

How it works: QwQ-32B is a version of Qwen2.5-32B that was fine-tuned to generate chains of thought using reinforcement learning (RL). Fine-tuning proceeded in two stages.

- The first stage of RL fine-tuning focused on math and coding tasks. The model earned rewards for correct final outcomes (no partial credit for intermediate steps). An accuracy verifier checked its math solutions, while a code-execution server verified generated code for predefined test cases.

- The second stage encouraged the model to follow instructions, use tools, and align its values with human preferences while maintaining math and coding performance, again rewarding final outcomes. In this stage, the model earned rewards from an unspecified reward model and some rule-based verifiers.

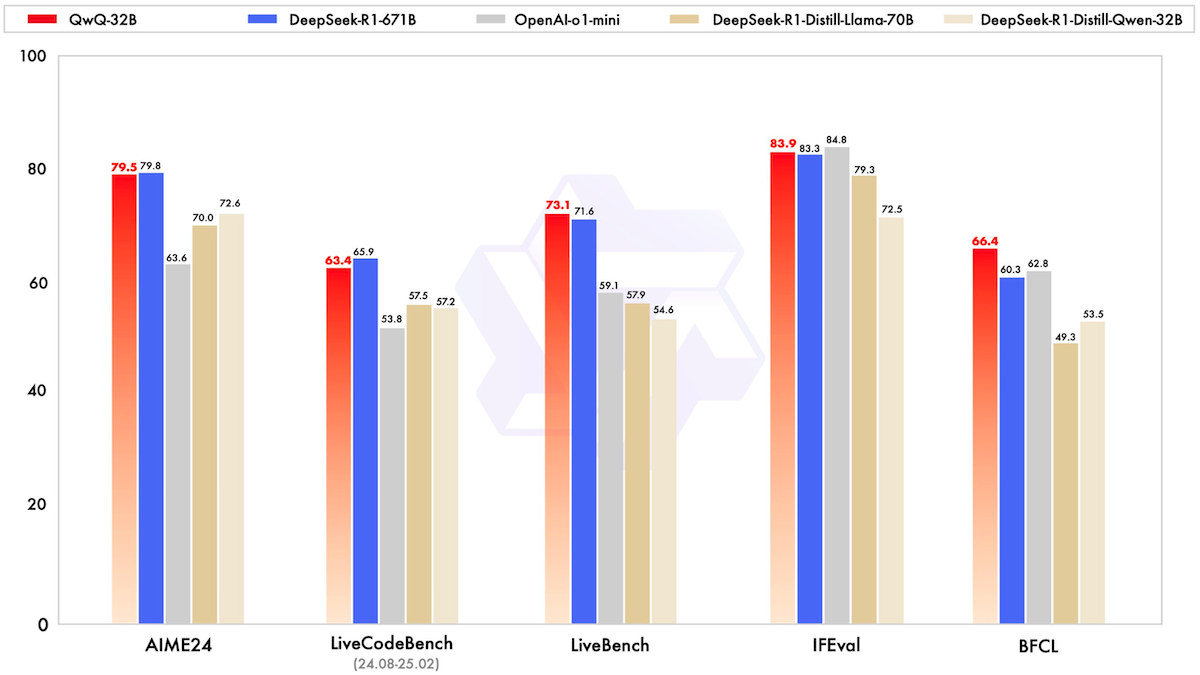

Performance: On several benchmarks for math, coding, and general problem solving, QwQ-32B outperforms OpenAI o1-mini (parameter count undisclosed) and achieves performance roughly comparable to DeepSeek-R1 (671 billion parameters, 37 billion active at any moment).

- On AIME24 (high-school competition math problems), QwQ-32B achieved 79.5 percent accuracy, well ahead of o1-mini (63.6 percent) but slightly behind DeepSeek-R1 (79.8 percent).

- On LiveCodeBench (code generation, repair, and testing), QwQ-32B achieved 63.4 percent, outperforming o1-mini (53.8 percent) but trailing DeepSeek-R1 (65.9 percent).

- On LiveBench (problem-solving in math, coding, reasoning, and data analysis), QwQ-32B reached 73.1 percent, ahead of o1-mini (59.1 percent) and DeepSeek-R1 (71.6 percent).

- On IFEval (following instructions), QwQ-32B achieved 83.9 percent, outperforming DeepSeek-R1 (83.8 percent) but behind o1-mini (84.8 percent).

- On BFCL (function calling), QwQ-32B achieved 66.4 percent, better than DeepSeek-R1 (60.3 percent), and o1-mini (62.8 percent).

Behind the news: DeepSeek’s initial model, DeepSeek-R1-Zero, similarly applied RL to a pretrained model. That effort produced strong reasoning but poor readability (for example, math solutions with correct steps but jumbled explanations). To address this shortcoming, the team fine-tuned DeepSeek-R1 on long chain-of-thought examples before applying RL. In contrast, QwQ-32B skipped preliminary fine-tuning and applied RL in two stages, first optimizing for correct responses and then for readability.

Why it matters: RL can dramatically boost LLMs’ reasoning abilities, but the order in which different behaviors are rewarded matters. Using RL in stages enabled the team to build a 32 billion parameter model — small enough to run locally on a consumer GPU — that rivals a much bigger mixture-of-experts model, bringing powerful reasoning models within reach for more developers. The Qwen team plans to scale its RL approach to larger models, which could improve the next-gen reasoning abilities further while adding greater knowledge.

We’re thinking: How far we’ve come since “Let’s think step by step”!

Microsoft Tackles Voice-In, Text-Out

Microsoft debuted its first official large language model that responds to spoken input.

What’s new: Microsoft released Phi-4-multimodal, an open weights model that processes text, images, and speech simultaneously.

- Input/output: Text, speech, images in (up to 128,000 tokens); text out (0.34 seconds to first token, 26 tokens per second)

- Performance: State of the art in speech transcription. Comparable to similar models in other tasks

- Knowledge cutoff: June 2024

- Architecture: transformer, 5.6 billion parameters

- Features: Text-image-speech processing, multilingual, tool use.

- Undisclosed: Training datasets, output size

- The company also released Phi-4-mini, an open weights 3.8 billion-parameter version of its biggest large language model (LLM), Phi-4. Phi-4-mini outperforms larger models including Llama 3.1 8B and Ministral-2410 8B on some benchmarks.

- Availability/price: Weights are free to download for noncommercial and commercial use under a MIT license.

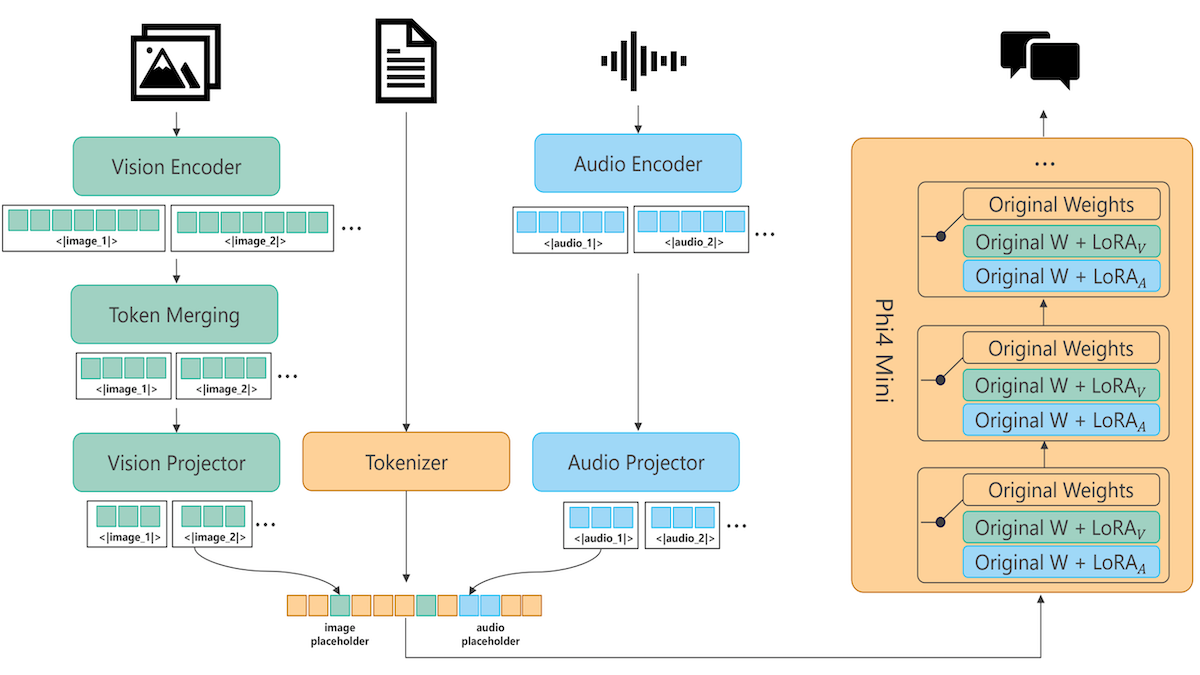

How it works: Phi-4-multimodal has six components: Phi-4-mini, vision and speech encoders as well as corresponding projectors (which modify the vision or speech embeddings so the base model can understand them), and two LoRA adapters. The LoRA adapters modify the base weights depending on the input: One adapter modifies them for speech-text problems, and one for vision-text and vision-speech problems.

- The speech encoder is a Conformer (which combines convolutional layers with a transformer) and the speech projector is a vanilla neural network. They trained Phi-4-multimodal to convert 2 million hours of speech to text, modifying only the speech encoder and projector. They further trained the system to convert speech to text, translate speech to other languages, summarize speech, and answer questions about speech, modifying only the speech encoder and the speech-text LoRA adapter.

- The vision encoder is based on a pretrained SigLIP-400M vision transformer, and the vision projector is a vanilla neural network. They trained the model to process text and images in four stages: (i) They trained Phi-4-multimodal to caption images, modifying only the vision projector. (ii) They trained the system on 500 billion tokens to caption images, transcribe text in images, and perform other tasks, modifying only the vision encoder and projector. (iii) They trained the system to answer questions about images, charts, tables, and diagrams and to transcribe text in images, modifying the vision encoder, project, and vision-text LoRA adapter. (iv) Finally, they trained the system to compare images and summarize videos, modifying only the vision projector and vision-text LoRA adapter.

- To adapt Phi-4-multimodal for images and speech, they trained the system to generate the text responses to a subset of the text-vision data that had been converted to speech-image using a proprietary text-to-speech engine, modifying only the text-vision LoRA adapter, vision encoder, and vision projector.

- Example inference: Given a question as speech and an image, the audio encoder and projector convert the speech to tokens, and the image encoder and projector convert the image into tokens. Given the tokens, Phi-4-multimodal, which uses the weights of Phi-4-mini modified by the vision-text/vision-speech LoRA adapter, generates a text response.

Results: The authors compared Phi-4-multimodal to other multimodal models on text-vision, vision-speech, text-speech tasks.

- Across 11 text-vision benchmarks, Phi-4-multimodal came in fourth out of 11 models. It outperformed Qwen2.5-VL-3B, Claude 3.5 Sonnet, and GPT 4o-mini. It trailed Qwen2.5-VL-7B, GPT-4o, and Gemini-2 Flash.

- Across four vision-speech benchmarks, Phi-4-multimodal outperformed by at least 6 percentage points Gemini-2.0-Flash, Gemini-2.0-Flash-Lite-preview, and InternOmni.

- Phi-4-multimodal outperformed all competitors in Microsoft’s report (including Qwen2-audio, Gemini 2.0 Flash, and GPT-4o) at transcribing speech from text in three datasets. It also achieved competitive performance in speech translation, outperforming its competitors on two of four datasets.

Behind the news: This work adds to the growing body of models with voice-in/text-out capability, including the open weights DiVA model developed by a team led by Diyi Yang at Stanford University.

Why it matters: The architectural options continue to expand for building neural networks that process text, images, audio, and various combinations. While some teams maintain separate models for separate data modalities, like Qwen2.5 (for text) and Qwen2.5-VL) (for vision-language tasks), others are experimenting with mixture-of-expert models like DeepSeek-V3. Phi-4-multimodal shows that Mixture-of-LoRAs is an effective approach for processing multimodal data — and gives developers a couple of new open models to play with.

We’re thinking: Output guardrails have been built to ensure appropriateness of text output, but this is difficult to apply to a voice-in/voice-out architecture. (Some teams have worked on guardrails that screen audio output directly, but the technology is still early.) For voice-based applications, a voice-in/text-out model can generate a candidate output without a separate, explicit speech-to-text step, and it accommodates text-based guardrails before it decides whether or not to read the output to the user.

Judge Upholds Copyright in AI Training Case

A United States court delivered a major ruling that begins to answer the question whether, and under what conditions, training an AI system on copyrighted material is considered fair use that doesn’t require permission.

What’s new: A U.S. Circuit judge ruled on a claim by the legal publisher Thomson Reuters that Ross Intelligence, an AI-powered legal research service, could not claim that training its AI system on materials owned by Thomson Reuters was a so-called “fair use.” Training the system did not qualify as fair use, he decided, because its output competed with Thomson Reuters’ publications.

How it works: Thomson Reuters had sued Ross Intelligence after the defendant trained an AI model using 2,243 works produced by Thomson Reuters without the latter’s permission. This ruling reversed an earlier decision in 2023, when the same judge had allowed Ross Intelligence’s fair-use defense to proceed to trial. In the new ruling, he found that Ross Intelligence’s use failed to meet the definition of fair use in key respects. (A jury trial is scheduled to determine whether Thomson Reuters' copyright was in effect at the time of the infringement and other aspects of the case.)

- Ross Intelligence’s AI-powered service competed directly with Thomson Reuters, potentially undermining its market by offering a derivative product without licensing its works. Use in a competing commercial product undermines a key factor in fair use.

- The judge found that Ross Intelligence’s use was commercial and not transformative, meaning it did not significantly alter or add new meaning to Thomson Reuters’ works — another key factor in fair use. Instead, it simply repackaged the works.

- The ruling acknowledged that Thomson Reuters’ works were not highly creative but noted that they possessed sufficient originality for copyright protection due to the editorial creativity and judgment involved in producing it.

- Although Ross Intelligence used only small portions of Thomson Reuters’ works, this did not weigh strongly in favor of fair use because those portions represented the most important summaries produced by Ross Intelligence.

Behind the news: The ruling comes amid a wave of lawsuits over AI training and copyright in several countries. Many of these cases are in progress, but courts have weighed in on some.

- The New York Times is suing OpenAI and Microsoft, arguing that their models generate output that competes with its journalism.

- Condé Nast, McClatchy, and other major publishers recently filed a lawsuit against Cohere, accusing it of using copyrighted news articles to train its AI models.

- Sony, UMG, and Warner Music filed lawsuits against AI music companies including Suno and Udio for allegedly using copyrighted recordings without permission.

- A judge dismissed key arguments brought by software developers who claimed that GitHub Copilot was trained on software they created in violation of open source licenses. The judge ruled in favor of Microsoft and OpenAI.

- In Germany, the publisher of the LAION dataset won a case in which a court ruled that training AI models on publicly available images did not violate copyrights.

Why it matters: The question of whether training (or copying data to train) AI systems is a fair use of copyrighted works hangs over the AI industry, from academic research to commercial projects. In the wake of this ruling, courts may be more likely to reject a fair-use defense when AI companies train models on copyrighted material to create output that overlaps with or replaces traditional media, as The New York Times alleges in its lawsuit against OpenAI. However, the ruling leaves room for fair use with respect to models whose output doesn’t compete directly with copyrighted works.

We’re thinking: Current copyright laws weren’t designed with AI in mind, and rulings like this one fill in the gaps case by case. Clarifying copyright for the era of generative AI could help our field move forward faster.

DeepSeek-R1 Uncensored

Large language models built by developers in China may, in some applications, be less useful outside that country because they avoid topics its government deems politically sensitive. A developer fine-tuned DeepSeek-R1 to widen its scope without degrading its overall performance.

What’s new: Perplexity released R1 1776, a version of DeepSeek-R1 that responds more freely than the original. The model weights are available to download under a commercially permissive MIT license.

How it works: The team modified DeepSeek-R1’s knowledge of certain topics by fine-tuning it on curated question-answer pairs.

- Human experts identified around 300 topics that are censored in China.

- The authors developed a multilingual classifier that spots text related to these topics.

- They identified 40,000 prompts that the classifier classified as sensitive with high confidence. They discarded those that contained personally identifiable information.

- For each prompt, they produced factual, chain-of-thought responses that mirrored DeepSeek-R1's typical reasoning processes.

- They fine-tuned DeepSeek-R1 on the resulting prompt-response pairs.

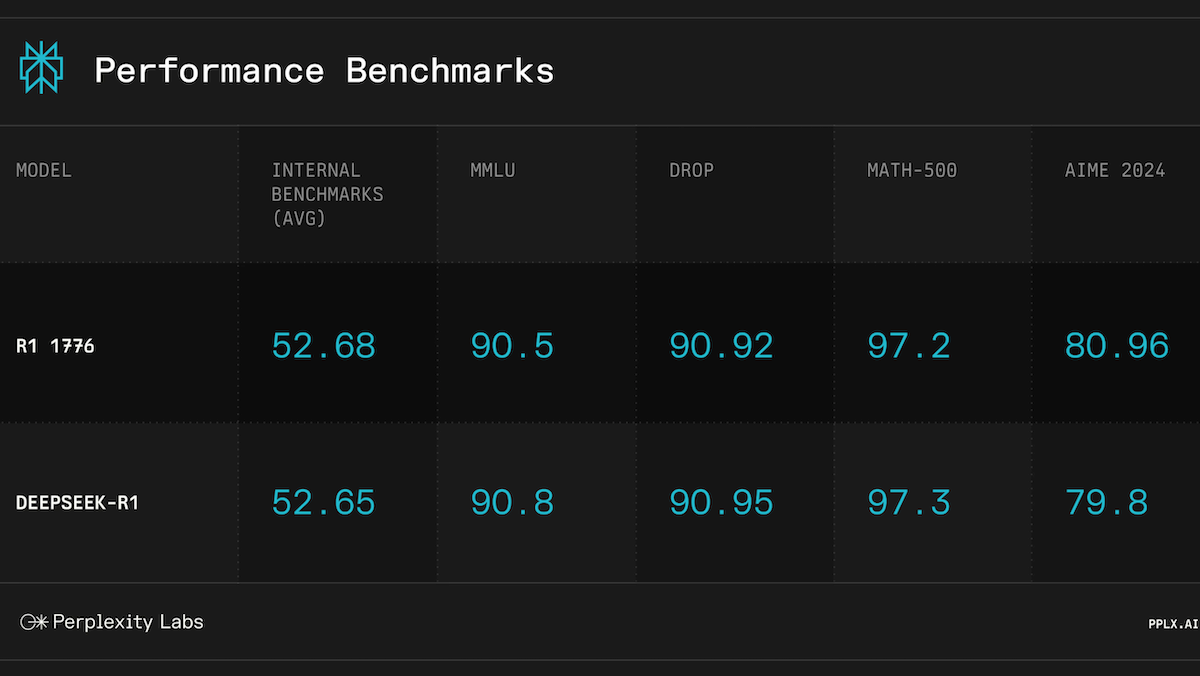

Results: The fine-tuned model responded to politically charged prompts factually without degrading its ability to generate high-quality output.

- The authors fed their model 1,000 diverse prompts that covered frequently censored topics. An unspecified combination of human and AI judges rated the models' responses according to the degree to which they are (i) evasive and (ii) censored outright.

- 100 percent of the fine-tuned model’s responses were rated uncensored, whereas the original version censored around 85 percent of sensitive queries. By comparison, DeepSeek-V3 censored roughly 73 percent, Claude-3.5-Sonnet around 5 percent, o3-mini about 1 percent, and GPT-4o 0 percent.

- Evaluated on four language and math benchmarks (MMLU, DROP, MATH-500, and AIME 2024) and unspecified internal benchmarks, the fine-tuned and original models performed nearly identically. Their scores differed by a few tenths of a percent except on AIME 2024 (competitive high-school math problems), where the fine-tuned model achieved 79.8 percent compared to the original’s 80.96 percent.

Behind the news: Among the first countries to regulate AI, China requires AI developers to build models that uphold “Core Socialist Values” and produce true and reliable output. When these objectives conflict, the political goal tends to dominate. While large language models built by developers in China typically avoid contentious topics, the newer DeepSeek models enforce this more strictly than older models like Qwen and Yi, using methods akin to Western measures for aligning output, like Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback and keyword filters.

Why it matters: AI models tend to reflect their developers’ values and legal constraints. Perplexity’s targeted fine-tuning approach addresses this barrier to international adoption of open-source models.

We’re thinking: As models with open weights are adopted by the global community, they become a source of soft power for their developers, since they tend to reflect their developers’ values. This work reflects a positive effort to customize a model to reflect the user’s values instead — though how many developers will seek out a fine-tuned version rather than the original remains to be seen.