Dear friends,

Last Friday on Pi Day, we held AI Dev 25, a new conference for AI Developers. Tickets had (unfortunately) sold out days after we announced their availability, but I came away energized by the day of coding and technical discussions with fellow AI Builders! Let me share here my observations from the event.

I'd decided to start AI Dev because while there're great academic AI conferences that disseminate research work (such as NeurIPS, ICML and ICLR) and also great meetings held by individual companies, often focused on each company's product offerings, there were few vendor-neutral conferences for AI developers. With the wide range of AI tools now available, there is a rich set of opportunities for developers to build new things (and to share ideas on how to build things!), but also a need for a neutral forum that helps developers do so.

Based on an informal poll, about half the attendees had traveled to San Francisco from outside the Bay Area for this meeting, including many who had come from overseas. I was thrilled by the enthusiasm to be part of this AI Builder community. To everyone who came, thank you!

Other aspects of the event that struck me:

- First, agentic AI continues to be a strong theme. The topic attendees most wanted to hear about (based on free text responses to our in-person survey at the start of the event) was agents!

- Google's Paige Bailey talked about embedding AI in everything and using a wide range of models to do so. I also particularly enjoyed her demos of Astra and Deep Research agents.

- Meta's Amit Sangani talked compellingly as usual about open models. Specifically, he described developers fine-tuning smaller models on specific data, resulting in superior performance than with large general purpose models. While there're still many companies using fine-tuning that should really just be prompting, I'm also seeing continued growth of fine-tuning in applications that are reaching scale and that are becoming valuable.

- Many speakers also spoke about the importance of being pragmatic about what problems we are solving, as opposed to buying into the AGI hype. For example, Nebius' Roman Chernin put it simply: Focusing on solving real problems is important!

- Lastly, I was excited to hear continued enthusiasm for the Voice Stack. Justin Uberti gave a talk about OpenAI’s realtime audio API to a packed room, with many people pulling out laptops to try things out themselves in code!

DeepLearning.AI has a strong “Learner First” mentality; our foremost goal is always to help learners. I was thrilled that a few attendees told me they enjoyed how technical the sessions were, and said they learned many things that they're sure they will use. (In fact, I, too, came away with a few ideas from the sessions!) I was also struck that, both during the talks and at the technical demo booths, the rooms were packed with attendees who were highly engaged throughout the whole day. I'm glad that we were able to have a meeting filled with technical and engineering discussions.

I'm delighted that AI Dev 25 went off so well, and am grateful to all the attendees, volunteers, speakers, sponsors, partners, and team members that made the event possible. I regretted only that the physical size of the event space prevented us from admitting more attendees this time. There is something magical about bringing people together physically to share ideas, make friends, and to learn from and help each other. I hope we'll be able to bring even more people together in the future.

Keep building!

Andrew

P.S. I'm thrilled to share our newest course series: the Data Analytics Professional Certificate! Data analytics remains one of the core skills of data science and AI, and this professional certificate takes you up to being job-ready for this. Led by Netflix data science leader Sean Barnes, this certificate gives you hands-on experience with essential tools like SQL, Tableau, and Python, while teaching you to use Generative AI effectively as a thought partner in your analyses. Labor economists project a 36% growth in data science jobs by 2033. I'm excited to see rising demand for data professionals, since working with data is such a powerful way to improve decision-making, whether in business, software development, or your private life. Data skills create opportunities at every level—I’m excited to see where they take you! Sign up here!

A MESSAGE FROM DEEPLEARNING.AI

The Data Analytics Professional Certificate is available now! This program equips you with data analytics skills—from foundations to job-ready. Learn statistical techniques combined with newly emerging generative AI workflows. Enroll now

News

Equally Fluent in Many Languages

Multilingual AI models often suffer uneven performance across languages, especially in multimodal tasks. A pair of lean models counters this trend with consistent understanding of text and images across major languages.

What’s new: A team at Cohere led by Saurabh Dash released Aya Vision, a family of multilingual vision-language models with downloadable weights in 8 billion- and 32-billion-parameter sizes.

- Input/output: Text and images in (up to 2,197 image tokens, up to 16,000 tokens total), text out (up to 4,000 tokens).

- Availability: Free via WhatsApp or Cohere Playground. Weights available to download, but licensed only for noncommercial uses.

- Features: Multilingual input and output in 23 languages.

- Undisclosed: Knowledge cutoff, training datasets, adapter architecture.

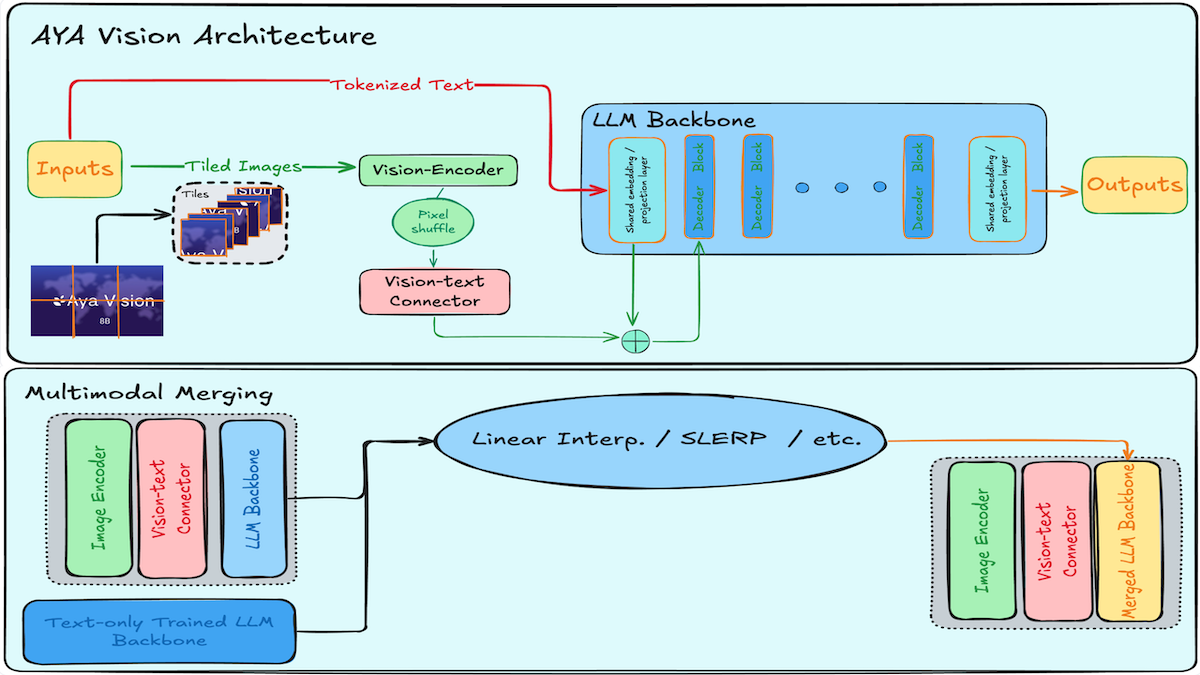

How it works: Each model comprises a pretrained large language model (Aya Expanse for the 32B model, C4AI Command R7B for the 8B version), a pretrained vision encoder (SigLIP 2), and a vision-language adapter (“connector”) of unspecified architecture.

- To establish basic vision-language understanding, the team froze the vision encoder and language model and trained the vision-language connector.

- They fine-tuned the vision-language connector and language model on multimodal tasks. To build the fine-tuning dataset, they generated synthetic annotations for various English-language datasets and translated a large amount of data into a variety of languages. They rephrased the translations to add fluency and variety, particularly for languages with little real-world data, by matching generated pairs with the original synthetic samples.

- They merged the language model with the fine-tuned vision-language model using an undisclosed method that preserved text capabilities while adding vision understanding.

- After proving this method for 8 billion parameters, they scaled up the recipe to 32 billion parameters.

Performance: To test the model, the team built and released two benchmarks: m-WildVision, a multilingual version of Wild Vision Bench’s arena-style competition for discussion of images, and AyaVisionBench, 135 image-question pairs in each language that cover nine tasks including captioning images, understanding charts, recognizing characters in images, visual reasoning, and converting screenshots to code. On these two benchmarks, Aya Vision 8B and 32B outperformed larger competitors, as judged by Claude 3.7 Sonnet.

- In head-to-head competitions on AyaVisionBench, Aya Vision 8B won up to 79 percent of the time against six competitors of similar size. On m-WildVision, it achieved 81 percent when compared to vision-language models of similar size including Qwen2.5-VL 7B, Pixtral 12B, Gemini Flash 1.5 8B, and Llama-3.2 11B Vision. Aya Vision 8B won 63 percent of the time against Llama-3.2 90B Vision, a model more than 10 times its size.

- On both benchmarks, Aya Vision 32B outperformed vision-language models more than twice its size including Llama-3.2 90B Vision, Molmo 72B, and Qwen2.5-VL 72B. On AyaVisionBench, it won between 50 and 64 percent of the time. On WildVision, it achieved win rates between 52 percent and 72 percent across all languages.

Behind the news: Aya Vision builds on the Cohere-led Aya initiative, a noncommercial effort to build models that perform consistently well in all languages, especially languages that lack high-quality training data. The project started with a multilingual text model (Aya Expanse), added vision (Aya Vision), and plans to eventually add video and audio.

Why it matters: Multilingual vision-language models often perform less well in low-resource languages, and the gap widens when they process media other than text. Aya Vision’s recipe for augmenting synthetic data with successively refined translations may contribute to more universally capable models. Aya Vision is available on the global messaging platform WhatsApp, where it can be used to translate text and images in all 23 of its current languages.

We’re thinking: Multilingual vision models could soon help non-native speakers decipher Turkish road signs, Finnish legal contracts, and Korean receipts. We look forward to a world in which understanding any scene or document is as effortless in Swahili as it is in English.

Science Research Proposals Made to Order

An AI agent synthesizes novel scientific research hypotheses. It's already making an impact in biomedicine.

What’s new: Google introduced AI co-scientist, a general multi-agent system designed to generate in-depth research proposals within constraints specified by the user. The team generated and evaluated proposals for repurposing drugs, identifying drug targets, and explaining antimicrobial resistance in real-world laboratories. It’s available to research organizations on a limited basis.

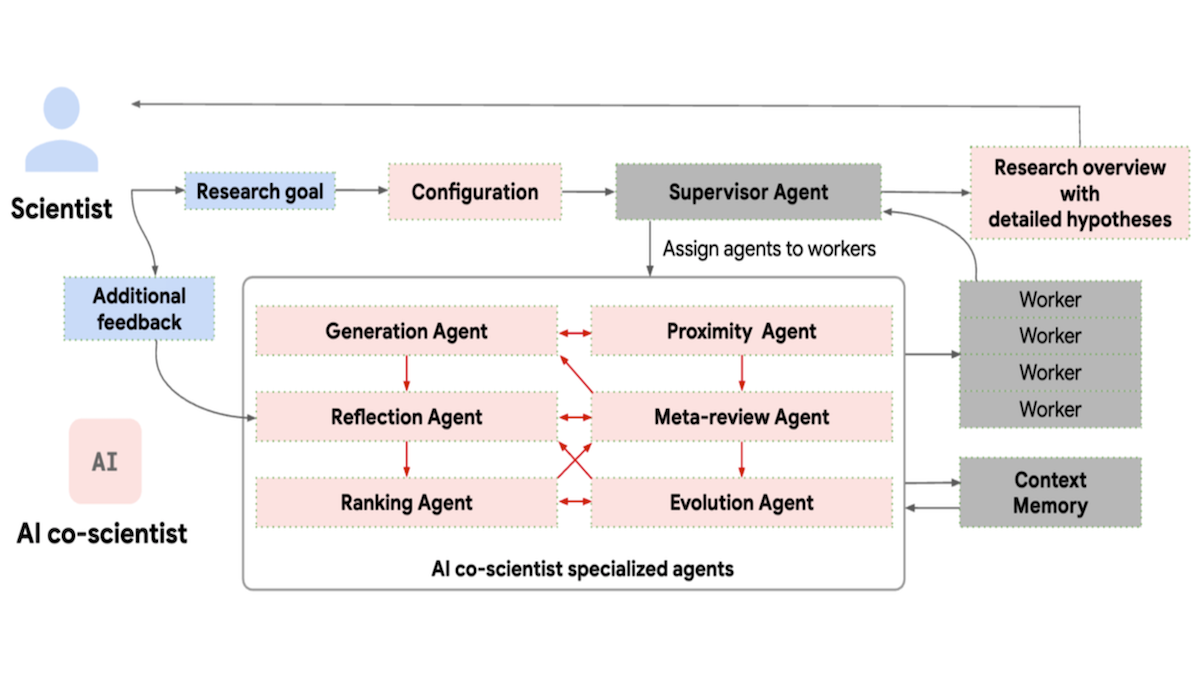

How it works: AI co-scientist accepts a text description of a research goal, including relevant constraints or ideas. In response, it generates research proposals and reviews, ranks, and improves them using seven agents based on Google’s Gemini 2.0 family of large language models. The completed proposals include sections that explain background, unmet needs, a proposed solution, goals, hypotheses, reasoning, study steps, and relevant articles. The agents take feedback and outputs from other agents to perform their prompted task simultaneously.

- The supervisor agent periodically determines how often to run the other six agents, how important their output is, and whether the system is finished. To accomplish this, it computes statistics that represent the number of proposals generated so far, how many have been reviewed, and so on.

- The generation agent generates a list of proposals. It searches the web for relevant research articles, identifies testable assumptions, and debates with itself to improve ambiguous statements and adhere to constraints.

- The reflection agent filters the generated proposals according to correctness, quality, safety, and novelty. First, it reviews a proposal without web search and discards obviously bad proposals. Then it reviews each proposal against literature it finds online. It breaks down and checks the proposal’s assumptions, checks whether the proposal might explain some observations in previous work, and simulates the proposed experiment (via text generation, similar to how a person performs a thought experiment).

- The proximity agents compute similarity between proposals to avoid redundancy.

- The ranking agent determines the best proposals according to a tournament. It examines one pair of proposals at a time (including reviews from the reflection agent) and debates itself to pick the better one. To save computation, it prioritizes comparing similar proposals, new proposals, and highest-ranking proposals.

- The evolution agent generates new proposals by improving existing ones. It does this in several different ways, including simplifying current ideas, combining top-ranking ideas, and generating proposals that are very different from current ones.

- The meta-review agent identifies common patterns in the reflection agent’s reviews and the ranking agent’s debates. Its feedback goes to the reflection and generation agents, which use it to address common factors in future reviews and avoid generating similar proposals, respectively.

Results: AI co-scientist achieved a number of impressive biomedical results in tests.

- Google researchers generated proposals for experiments that would repurpose drugs to treat acute myeloid leukemia. They shared the 30 highest-ranked proposals with human experts, who chose five for lab tests. Of the five drugs tested, three killed acute myeloid leukemia cells.

- Experts selected three among 15 top-ranked generated proposals that proposed repurposing existing drugs to treat liver fibrosis. Two significantly inhibited liver fibrosis without being toxic to general cells. (Prior to this research, one of the drugs was approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration for a different illness, which may lead to a new treatment for liver fibrosis.)

- AI co-scientist invented a hypothesis to explain how microbes become resistant to antibiotics. Human researchers had proposed and experimentally validated the same hypothesis, but their work had not yet been published at the time, and AI co-scientist did not have access to it.

Behind the news: A few AI systems have begun to produce original scientific work. For instance, a model generated research proposals that human judges deemed more novel than proposals written by flesh-and-blood scientists, and an agentic workflow produced research papers that met standards for acceptance by top conferences.

Why it matters: While previous work used agentic workflows to propose research ideas on a general topic, this work generates proposals for specific ideas according to a researcher’s constraints (for example, a researcher could specify that a novel medical treatment for a specific disease only consider drugs already approved for human trials for other uses) and further instructions. AI co-scientist can take feedback at any point, allowing humans to collaborate with the machine: People provide ideas, feedback, and guidance for the model, and the model researches and proposes ideas in return.

We’re thinking: I asked my AI system to propose a new chemical experiment. But there was no reaction!

Some AI-Generated Works Are Copyrightable

The United States Copyright Office determined that existing laws are sufficient to decide whether a given AI-generated work is protected by copyright, making additional legislation unnecessary.

What’s new: AI-generated works qualify for copyright if a human being contributed enough creative input, according to the second part of what will be a three-part report on artificial intelligence and copyright law.

How it works: The report states that “the outputs of generative AI can be protected by copyright only where a human author has determined sufficient expressive elements.” In other words, humans and AI can collaborate on creative works, but copyright protection applies only if a human shapes the AI-generated material beyond simply supplying a prompt.

- The report rejects the argument that protecting AI-generated works requires a new legal framework. Instead, it argues that copyright law already establishes clear standards of authorship and originality.

- Human authors or artists retain copyright over creative contributions in the form of selection, coordination, and modification of generated outputs. Selection refers to curating AI-generated elements. Coordination involves organizing multiple generated outputs into a cohesive work. Modification is altering generated material in a way that makes it original. They retain copyright even if AI processes their creative work. They lose it only if the generated output is genuinely transformative.

- The report emphasizes continuity with past decisions regarding computer-assisted works. It cites a February 2022 ruling in which the Copyright Office rejected a work that had no human involvement. However, in 2023, the office granted a copyright to a comic book that incorporated AI-generated images because a human created original elements such as text, arrangement, and modifications. The report argues this approach aligns with prior treatment of technologies like photography: Copyright protection depends on identifiable human creative input, and that input merits protection even if technology assists in producing it.

Behind the news: The first part of the Copyright Office’s report on digital replicas, or generated likenesses of a person’s appearance and voice. It found that existing laws don’t provide sufficient protection against unauthorized digital replicas and recommended federal legislation to address the gap. Its findings influenced ongoing discussions in Congress, where proposed bills like the No AI FRAUD Act and the NO FAKES Act aim to regulate impersonation via AI. Additionally, industry groups such as the Authors Guild and entertainment unions have pursued their own agreements with studios and publishers to safeguard performers, artists, and authors from unauthorized digital reproduction. However, no federal law currently defines whether copyright can protect a person’s likeness or performance.

Why it matters: The Copyright Office deliberately avoided prescribing rigid criteria for the types or degrees of human input that are sufficient for copyright. Such determinations require nuanced evaluation case by case. This flexible approach accommodates the diverse ways creative people use AI as well as unforeseen creative possibilities of emerging technology.

We’re thinking: Does copyright bar the use of protected works to train AI systems? The third part of the Copyright Office’s report — no indication yet as to when to expect it — will address this question. The answer could have important effects on both the arts and AI development.

Designer Materials

Materials that have specific properties are essential to progress in critical technologies like solar cells and batteries. A machine learning model designs new materials to order.

What’s new: Researchers at Microsoft and Shenzhen Institute of Advanced Technology proposed MatterGen, a diffusion model that generates a material’s chemical composition and structure from a prompt that specifies a desired property. The model and code are available under a license that allows commercial as well as noncommercial uses without limitation. The training data also is noncommercially available.

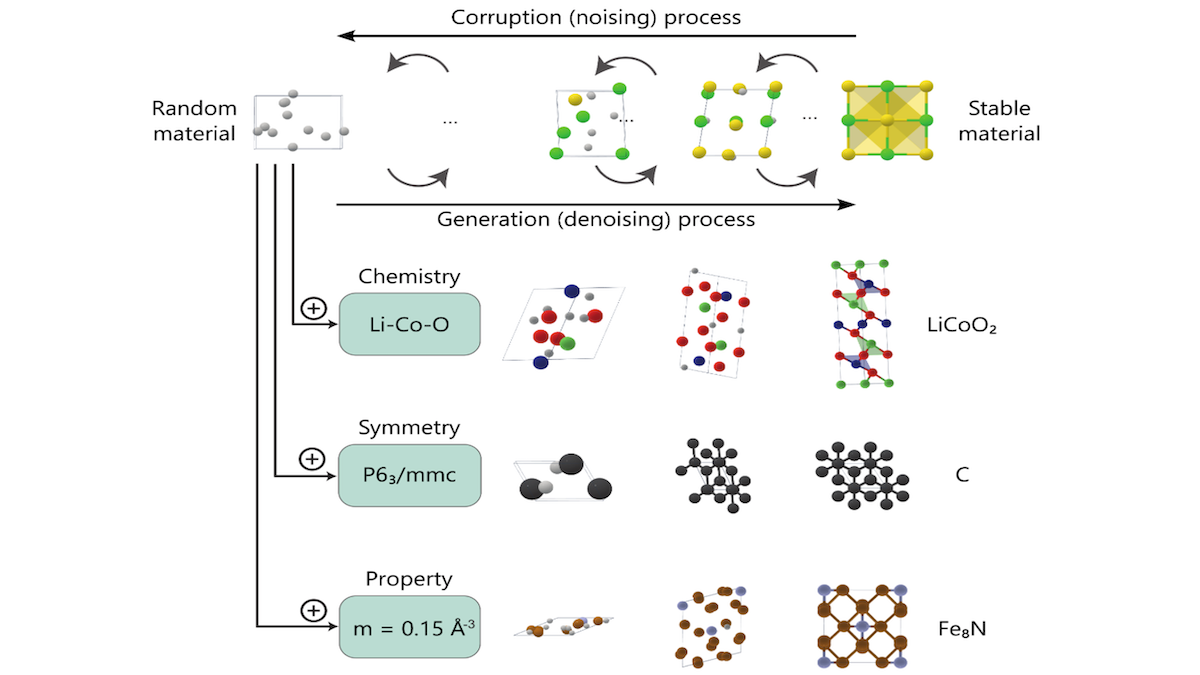

How it works: MatterGen’s training followed a two-stage process. In the first stage, it learned to generate materials (specifically crystals — no liquids, gasses, or amorphous solids like glass). In the second, it learned to generate materials given a target mechanical, electronic, magnetic, or chemical property such as magnetic density or bulk modulus (the material’s resistance to compression).

- MatterGen first learned to remove noise that had been added to 600,000 examples drawn from two datasets. Specifically, it learned to remove noise from three noisy matrices that represented a crystal’s shape (parallelepiped), the type of each atom, and the coordinates of each atom.

- To incorporate information about properties, the authors added to the diffusion model four vanilla neural networks, each of which took an embedding of the target property. The diffusion model added the output of these networks to its intermediate embeddings at different layers.

- Then the authors fine-tuned the system to remove added noise from materials that contained property information in their original dataset.

- At inference, given three matrices of pure noise representing crystal shape, atom types, and atom coordinates, and a prompt specifying the desired property, the diffusion model iteratively removed the noise from all three matrices.

Results: The authors generated a variety of materials, and they synthesized one to test whether it had a target property. Specifically, they generated over 8,000 candidates with the target bulk modulus of 200 gigapascals (a measure of resistance to uniform compression), then automatically filtered them based on a number of factors to eliminate material in their dataset and unstable materials. Of the remaining candidates, they chose four manually and successfully synthesized one. The resulting crystal had a measured bulk modulus of 158 gigapascals. (Most materials in the dataset had a bulk modulus of between 0 and 400 gigapascals.)

Behind the news: Published in 2023, DiffCSP also uses a diffusion model to generate the structures of new materials. However, it does so without considering their desired properties.

Why it matters: Discovering materials relies mostly on searching large databases of existing materials for those with desired properties or synthesizing new materials and testing their properties by trial and error. Designing new crystals with desired properties at the click of a button accelerates the process dramatically.

We’re thinking: While using AI to design materials accelerates an important step, determining whether a hypothesized material can be manufactured efficiently at scale is still challenging. We look forward to research into AI models that also take into account ease of manufacturing.

A MESSAGE FROM DEEPLEARNING.AI

In our latest short course, Long-Term Agentic Memory with LangGraph, learn how to integrate semantic, episodic, and procedural memory into AI workflows. Guided by Harrison Chase, you’ll build a personal email agent with routing, writing, and scheduling tools to automatically ignore and respond to emails, while keep track of facts and past actions over time. Join in for free