Dear friends,

Fine-tuning small language models has been gaining traction over the past half year. I’d like to share my sense of when to use this technique, and also when not to, based on what I’m seeing in multiple companies.

First, while fine-tuning is an important and valuable technique, many teams that are currently using it probably could get good results with simpler approaches, such as prompting (including writing mega prompts), few-shot prompting, or simple agentic workflows.

Why shouldn’t these teams be fine-tuning? Because fine-tuning, which takes a pre-trained model and further trains it on data specific to an application, is relatively complex to implement. You need to collect training data, then (unless you want to implement fine-tuning yourself) find a provider to help with running fine-tuning, then find a way to deploy the fine-tuned model. Because it adds extra complexity both in training and deployment, usually I resort to this technique only after I find that prompting and simple agentic workflows are not up to a task.

Having said that, there are also applications where fine-tuning is appropriate and valuable. LoRA (which learns by modifying a limited number of parameters rather than the entire model) and related methods have made fine-tuning quite affordable, particularly for small models (say, 13B or fewer parameters). And the amount of data needed to get started is less than most people think. Depending on the application, I’ve seen good results with 100 or even fewer examples. Here are a few applications where I have seen fine-tuning applied successfully:

Improving accuracy of critical applications. Prompting can get you really far for many applications. But sometimes, fine-tuning helps eke out that last bit of accuracy. For example, if you are building a customer service chatbot and need it to call the right API reliably (say, to carry out transactions, issue refunds, and the like), perhaps prompting can get it to make the right API call 95% of the time. But if you struggle to raise the accuracy even with revisions to the prompt and you really need 99% accuracy, fine-tuning on a dataset of conversations and API calls might be a good way to get you there. This is particularly true for tasks where it's hard to specify, using only language, an unambiguous rule to decide what to do. For example, when a customer is frustrated, should the chatbot escalate to a manager or just issue a refund? Teams often write Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for human workers to follow, and these SOPs can go into the prompts of models. But if it is hard to specify an unambiguous SOP, so even humans need to see numerous examples before they can learn what to do, fine-tuning can be a good approach. For many text-classification applications fine-tuning also works well, for example, classifying medical records into diagnosis and procedure codes for health insurance claims.

Learning a particular style of communication. As I explain in “Generative AI for Everyone,” my team fine-tuned a model to sound like me. Many people (including myself) have idiosyncratic uses of language. There are certain words I tend to say and others I tend not to, and these idiosyncrasies are numerous and very difficult to specify in a text prompt. (By the way, the avatar at deeplearning.ai/avatar, built with RealAvatar, uses fine-tuning for this reason.) To get a system to communicate in a certain style, fine-tuning is often a superior solution to prompting alone.

Reducing latency or cost during scale-ups. I’ve seen applications where developers have successfully prompted a large model to perform a complex task. But as usage scales up, if the large model is too slow (which often happens) or too expensive (which also happens but less frequently), the team might want to use a smaller model. If, however, the performance of the smaller model isn't good enough, then fine-tuning it can help bring it up to the performance of the larger one for that narrow application. Further, the larger model (or perhaps an agentic workflow) can also be used to generate data to help with fine-tuning the small model for that task.

At the cutting edge of research, some teams are fine-tuning models to get better at a certain language. But with few exceptions, if the goal is to get an LLM to better understand a body of knowledge that is not in its training data, I find that using RAG (retrieval augmented generation) is a much simpler approach, and I still occasionally run into teams using fine-tuning for which I think RAG would work better.

Overall my sense is that, of all the teams I see using fine-tuning, perhaps 75% could get good results using simpler techniques (like prompting or agentic workflows), but in 25% of cases I know of no better way to achieve their goal.

It is still technically challenging to implement fine-tuning, get the hyperparameters right, optimize the compute resources, and so on. We are lucky that more and more companies have worked hard to optimize these and provide efficient fine-tuning services. Many of them allow us to fine-tune open weights models and also download the fine-tuned weights. Some allow us to fine-tune their closed models and continue to keep the tuned weights closed. Both can be useful, but the former has obvious advantages of portability and not having to worry that the provider will stop serving a particular model, causing a critical component in our software to become deprecated.

In conclusion, before fine-tuning, consider if you should be trying just a bit harder with prompting or agentic workflows, which can lead to simpler solutions that are easier to maintain. The vast majority of applications my teams build do not use any fine-tuning at all, but it’s a critical piece of a small minority of them.

Keep learning!

Andrew

A MESSAGE FROM DEEPLEARNING.AI

In “Vibe Coding 101 with Replit,” you’ll learn to plan, prompt, and debug alongside a coding agent. Build, host, and share two real web apps in Replit’s cloud environment while developing effective development skills like writing product requirements, structuring tasks, and refining AI-generated code. Start today

News

Vision-Language, Compact and Open

Google updated its open-weights family of large language models to include versions that handle image and video inputs.

What’s new: Google released its Gemma 3 multilingual large language models with parameter counts of 1 billion, 4 billion, 12 billion, and 27 billion. While the smallest processes text only, the other three are vision-language models that are small enough to run on a consumer hardware.

- Input/output: Gemma 3 1B: text-in (up to 32,000 tokens), text out (up to 8,192 tokens). Gemma 3 4B, 7B, 27B: text, images/video in (up to 128,000 tokens), text out (up to 8,192 tokens). Gemma 3 27B outputs 24.61 tokens per /second, 0.68 seconds to first token.

- Knowledge cutoff: March 2024

- Architecture: Gemma 3 1B: Transformer. Gemma 3 4B, 12B, 27B: Transformer, SigLIP vision encoder.

- Features: 140 languages, function calling, structured output.

- Training data: Gemma 3 1B: 2 trillion tokens of web text, code, and mathematics. Gemma 3 4B, 12B, 27B: between 4 trillion and 14 trillion tokens of text and images.

- Availability/price: Weights free to download from Hugging Face and Kaggle under a license that allows noncommercial and commercial uses with some restrictions. Available free via Google’s AI Studio.

How it works: Gemma 3 rearchitects and refines earlier Gemma models for higher performance at lower parameter counts.

- To save memory, Gemma 3 interleaves five local attention layers for every global attention layer. Global attention layers attend to the entire input, while local attention layers attend to 1,024 tokens.

- The models were fine-tuned to encourage their outputs to match those of an unspecified larger teacher model.

- Gemma 3 learned via reinforcement learning in three ways. (i) The models were aligned with human preferences via reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF). (ii) They were fine-tuned to solve math problems via reinforcement learning, much like DeepSeek-R1. (iii) They were trained to generate better code via reinforcement learning from execution feedback (RLEF). Specifically, over several rounds of output, RLEF tested generated code on a subset of tests, then prompted the model to fix any bugs. RLEF rewarded the models if their final output passed all tests.

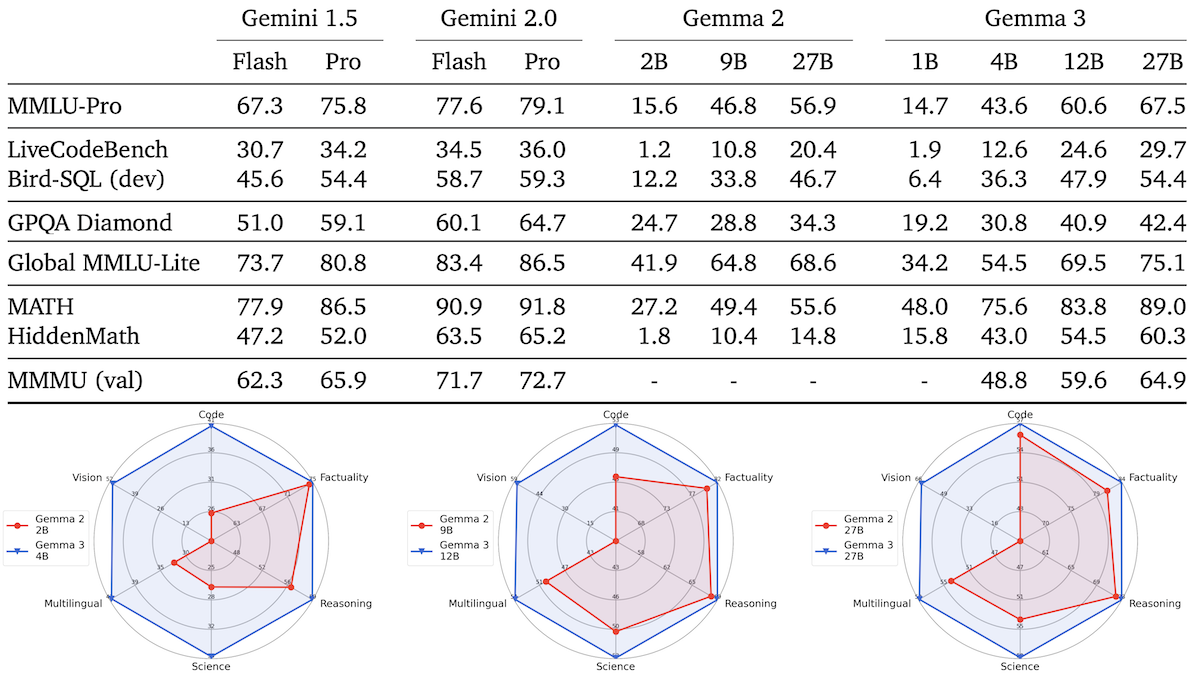

Performance: Gemma 3 models outperform Gemma 2 models of equal or larger size by several measures, and all sizes show a strong ability to solve mathematics word problems as measured by MATH.

- In Google’s tests, Gemma 3 1B performs roughly comparably to Gemma 2 2B, outperforming the larger model on LiveCodeBench (1.9 percent to 1.2 percent) and MATH (48.0 percent to 27.2 percent).

- Gemma 3 4B achieves roughly comparable performance to Gemma 2 9B, Llama 3.1 8B, and Qwen2.5-7B. It’s slightly behind Microsoft Phi-4 Mini (also 4 billion parameters), except on MATH, according to that company’s tests.

- Gemma 3 12B improves on Gemma 2 27B and compares to Gemini 1.5 Flash (in TIGER-Lab’s tests) and Anthropic Claude 3.5 Haiku (in that developer’s tests). It outperforms the larger, proprietary models on MATH.

- Gemma 3 27B consistently outperforms the Gemma 2 model of the same size and performs comparably to Gemini 1.5 Pro on MMLU-Pro (high-level language comprehension) 67.5 percent to 56.9 percent, on LiveCodeBench (coding) 29.7 percent to 20.4 percent, on GPQA Diamond (graduate-level domain knowledge) 42.4 percent to 34.3 percent, and on MATH 89.0 percent to 55.6 percent.

- Moreover, Gemma 3 27B achieves 1,338 ELO in Chatbot Arena, a top-ten score that puts it ahead of OpenAI o1 and behind only DeepSeek-R1 among models with open weights.

Hot on Gemma 3’s heels: Shortly after Gemma 3 became available, Mistral released Small 3.1 (24 billion parameters), a vision-language model with open weights, under a more permissive Apache 2.0 license.

- Mistral Small 3.1 is similarly multilingual and offers a 128,000 token context window.

- It slightly outperforms Gemma 3 27B on MMLU, MMLU-Pro, MMMU, and other selected benchmarks.

- It also outperforms Gemma 3 27B and other models in its size range on long-context tests. (However, Gemma 3 27B performs better in the Chatbot Arena test of human preference.)

Why it matters: Gemma 3 takes advantage of a variety of techniques to raise the bar for vision-language performance in relatively small models. Knowledge distillation, multiple rounds of reinforcement learning, and fine-tuning on many languages are a powerful combination.

We’re thinking: A vision-language model small enough to run on a smartphone feels increasingly close!

Better Images in Fewer Steps

Diffusion models usually take many noise-removal steps to produce an image, which takes time at inference. There are ways to reduce the number of steps, but the resulting systems are less effective. Researchers devised a streamlined approach that doesn’t sacrifice output quality.

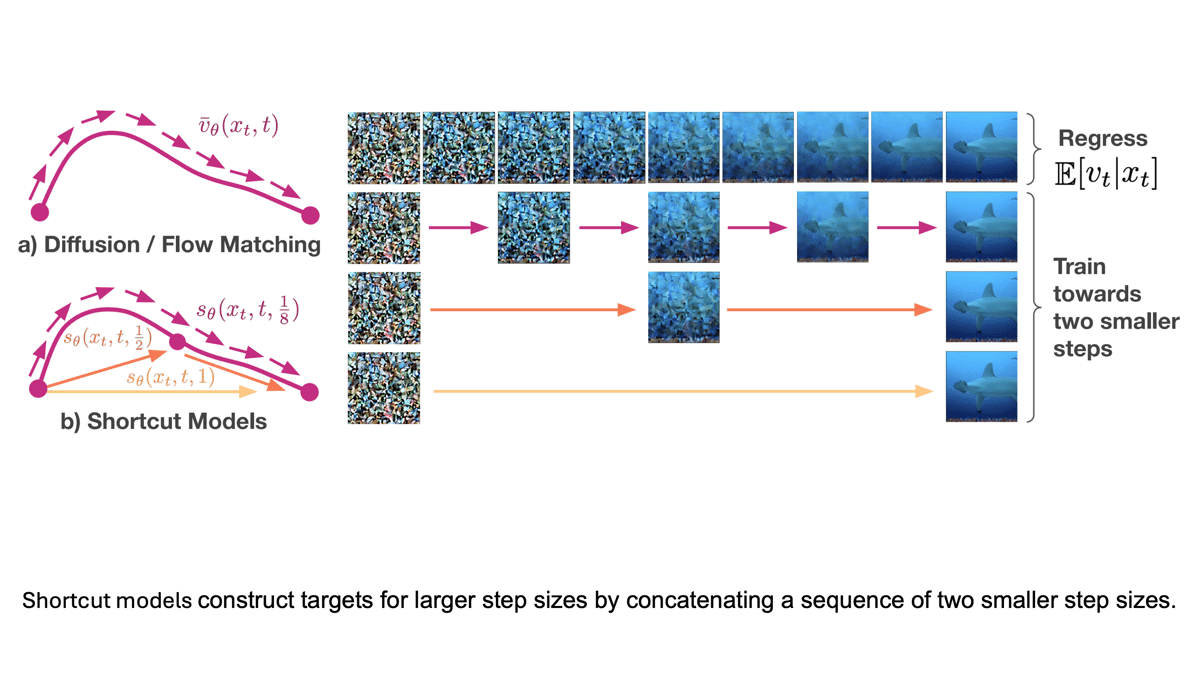

What’s new: Kevin Frans and colleagues at UC Berkeley introduced shortcut models that learn to take larger noise-removal steps and thus require fewer steps to generate an image.

Key insight: At inference, a scheduler like Euler can enable a model to take larger steps than those it learned during training, but this approach yields worse performance. Alternatively distillation, in which a student model learns to remove the same amount of noise as a teacher model when it takes several steps, offers improved performance at the cost of more cumbersome development. Training the model directly to take bigger steps — that are equivalent to multiple smaller steps — enables it to maintain high performance while taking fewer steps.

How it works: The authors trained DiT-B, a diffusion transformer, to generate images like those in CelebA-HQ (celebrity faces) and ImageNet-256 (various subjects, size 256x256).

- The loss function included terms for flow matching and self-consistency. The flow matching term encouraged the model to learn to remove noise. The self-consistency term encouraged the model to learn how to minimize the discrepancy between the noise removed by a single big step and two smaller steps.

- Initially the model learned to combine two small steps into one step 2x as large. Combining two larger steps resulted in step sizes of 4x, 8x, and so on, up to 128x.

- At inference, the user told the model how many small steps to take, and the model computed the single-step size necessary to accomplish that.

Results: The authors compared their model using 1, 4, or 128 steps to alternatives that were trained via various methods including many variants of distillation. They measured the results using Fréchet inception distance (FID), which assesses how closely generated images resemble real-world images (lower is better).

- On both CelebA-HQ and ImageNet-256, their model, when it took four steps, achieved the best performance. For example, on CelebA-HQ, using four steps, the shortcut model achieved 13.8 FID, while the next-best model, Reflow (another variant of distillation), achieved 18.4 FID.

- When it took one step, it achieved the second-best result, behind progressive distillation, which trained a series of student models to remove the same amount of noise as a teacher model does when it takes multiple steps.

Why it matters: Generating images by diffusion is typically costly, and previous approaches to cutting the cost have compromised either performance or incurred additional development expense or both. This method achieves high performance at relatively low cost.

We’re thinking: As diffusion models continue to become cheaper and faster, we expect to see applications blossom!

LLM Support for Tutors

Students benefit from tutoring, but training tutors is expensive. A study shows that large language models can boost tutors’ effectiveness in real time.

What’s new: Rose Wang and colleagues at Stanford built Tutor CoPilot, a tool for remote, online tutors that uses GPT-4 to generate hints, explanations, questions, and other helpful responses to students.

Key insight: When a student makes an error, according to previous work by some of the same authors, effective teachers choose a strategy for addressing the mistake. The authors identified 11 strategies, such as ask a question, explain a concept, provide a hint, or encourage the student. Moreover, they found that an LLM that executed a strategy chosen by an expert teacher performed significantly better than an LLM that was prompted with a strategy chosen at random or no specific strategy. Letting inexperienced tutors choose a strategy while an LLM generates a response helps them learn how to execute the strategy. Students, in turn, benefit from responses that mimic those of an experienced teacher.

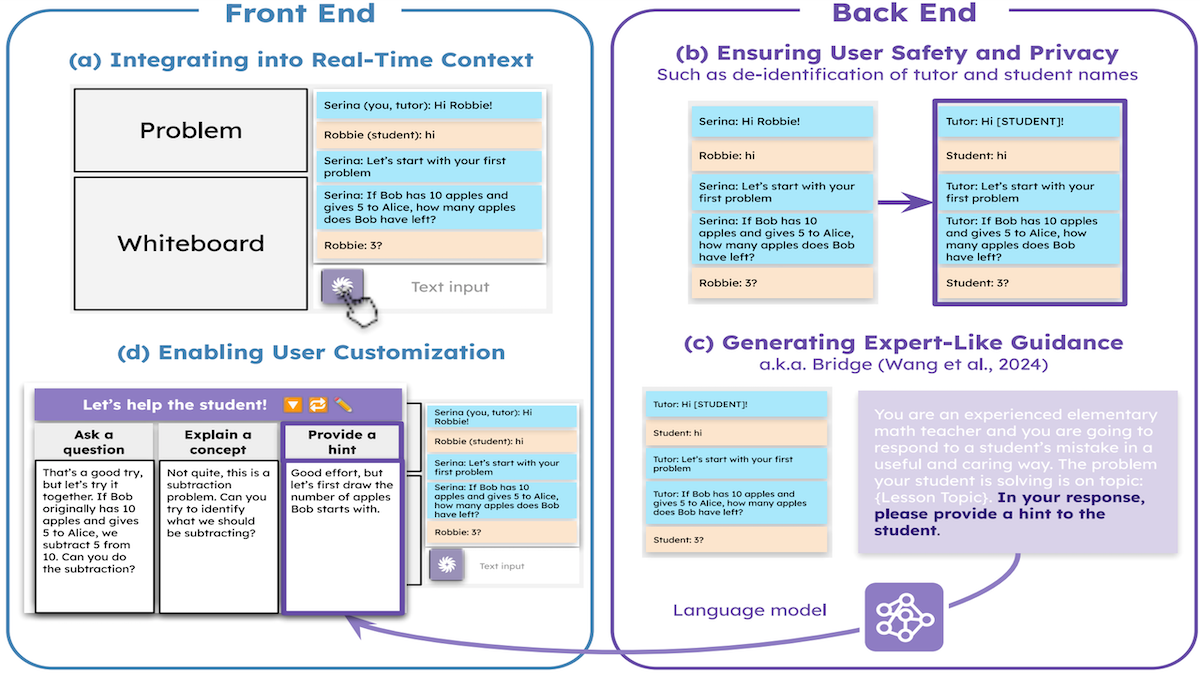

How it works: The authors outfitted a remote tutoring application with GPT-4.

- The application included a tutor-student chat window, a problem display, and a whiteboard. The authors added a button that enabled the tutor to turn Tutor CoPilot on or off.

- When a tutor engaged Tutor CoPilot, the system prompted GPT-4 to behave as an experienced elementary math teacher and provided context in the form of the 10 most recent messages, the current lesson topic, and a default strategy from the list. GPT-4 responded with guidance. (To preserve the tutor’s and student’s privacy, the system redacted their names using the open source library Edu-ConvoKit.)

- The system prompted GPT-4 three times, each time changing the strategy, and presented the tutor with three potential responses.

- The tutor could re-generate or edit GPT-4’s responses, or select a strategy and generate a new response before adding it to the chat window.

Results: The authors partnered with a virtual tutoring company and a school district in the United States for a two-month study of 874 tutors and 1,787 students between grades 3 and 8. They divided the participants into two groups. In one group, tutors conducted sessions with students as usual. In the other, tutors had access to Tutor CoPilot. The authors measured success by the percentage of students who passed a test at the end of a lesson.

- In the group that didn’t use Tutor CoPilot, 62 percent of students passed the test.

- In the group with TutorCopilot, 66 percent passed.

- The effect was most pronounced among the one-third of tutors who had the lowest ratings (9 percent higher) and least experience (7 percent higher).

- The API cost was approximately $3.31 per tutor, or roughly $20 per tutor per year.

Yes, but: The authors found statistically significant improvements as measured by test results per lesson, but not in end-of-year exam results. The study’s two-month duration may account for the lack of evidence for longer-term effects.

Why it matters: LLMs hold great promise for helping to educate students, but they also show potential in educating teachers. For inexperienced tutors who are learning how to interact with students, an LLM’s general knowledge and pedagogical insights gleaned from expert teachers make a powerful combination.

We’re thinking: Although it relies on sophisticated technology, the authors’ approach is simple: Prompt an LLM to apply proven teaching principles. Presumably such principles apply beyond elementary math, which would make this approach useful for teaching a variety of disciplines.

Faster Learning for Diffusion Models

Diffusion transformers learn faster when they can look at embeddings generated by a pretrained model like DINOv2.

What’s new: Sihyun Yu and colleagues at Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology, Korea University, New York University, and Scaled Foundations (a startup that builds AI for robotics) proposed Representation Alignment (REPA), a loss term for transformer-based diffusion.

Key insight: Diffusion models learn to remove noise from images to which noise was added (and, at inference, they start with pure noise to generate a fresh image). This process can be divided into two parts: learning to (i) embed the noisy image and (ii) estimate the noise from the embedding. One way to accelerate learning is to add a loss term that encourages the diffusion model to produce embeddings that are similar to those produced by a pretrained embedding model. The diffusion model can learn to estimate the noise faster if it doesn’t need to learn how to embed an image from scratch.

How it works: The authors modified DiT-XL/2 and SiT-XL/2 transformer-based latent diffusion models, a class of diffusion models that subtract noise from embeddings rather than images. They trained the models to produce images similar to ImageNet. In the process, the modified models learned to produce embeddings similar to those produced by a pretrained DINOv2.

- The authors used Stable Diffusion VAE’s pretrained encoder to embed an image.

- Given the embedding with noise added, the diffusion model learned to remove the noise according to the usual loss term.

- It also learned according to the REPA loss. Specifically, it learned to maximize the cosine similarity between a specially processed version of its eighth-layer embedding and the embedding produced by a pretrained DINOv2. To process its eighth-layer embedding for the REPA loss, the diffusion model fed the embedding to a vanilla neural network.

- At inference, given pure noise, the model removed it over several steps to produce an image embedding. Stable Diffusion VAE’s decoder converted the embedding into an image.

Results: The modified DiT-XL/2 learned significantly faster than the unmodified version.

- In 400,000 training steps, the modified model reached 12.3 Fréchet inception distance (FID) (which measures similarity between generated and non-generated images, lower is better), while the unmodified version reached 19.5 FID.

- The models continued to learn at different speeds as training continued. The modified DiT-XL/2 took 850,000 training steps to reach 9.6 FID, while the unmodified version took 7 million steps to reach the same number.

- Experiments with modified and unmodified versions of SiT-XL/2 yielded similar results.

- Trained to convergence, the modified models outperformed the unmodified versions. For instance, the modified SiT-XL/2 achieved 5.9 FID (after 4 million training steps), while the unmodified version achieved 8.3 FID (after 7 million training steps).

Why it matters: Diffusion models and contrastive self-supervised models like DINOv2 have fundamentally different training objectives: One produces embeddings for the purpose of image generation, while the other’s embeddings are used for tasks like classification and semantic segmentation. Consequently, they learn different aspects of data. This work proposes a novel way to combine these approaches to produce more generally useful embeddings.

We’re thinking: It turns out that the REPA modification enabled diffusion models to produce embeddings better suited not only to diffusion but also to image classification and segmentation. A similar approach could lead to a more holistic framework for learning image representations.