Dear friends,

I am so sorry that the U.S. is letting down our friends and allies. Broad tariffs, implemented not just against adversaries but also steadfast allies, will damage the livelihoods of billions of people, create inflation, make the world more fragmented, and leave the U.S. and the world poorer. AI isn’t the solution to everything, but even amidst this challenging environment, I hope our community can hold together, keep building friendships across borders, keep sharing ideas, and keep supporting each other.

Much has been written about why high, widespread taxes on imports are harmful. In this letter, I’d like to focus on its possible effects on AI. One silver lining of the new tariffs is that they focus on physical imports, rather than digital goods and services, including intellectual property (IP) such as AI research inventions and software. IP is difficult to tax, because each piece of IP is unique and thus hard to value, and it moves across borders with little friction via the internet. Many international AI teams collaborate across borders and timezones, and software, including specifically open source software, is an important mechanism for sharing ideas. I hope that this free flow of ideas remains unhampered, even if the flow of physical goods is.

However, AI relies on hardware, and tariffs will slow down AI progress by restricting access to it. Even though a last-minute exception was made for semiconductors, taxing imports of solar panels, wind turbines, and other power-generation and -distribution equipment will diminish the ability to provide power to U.S. data centers. Taxing imports of servers, cooling hardware, networking hardware, and the like will also make it more expensive to build data centers. And taxing consumer electronics, like laptops and phones, will make it harder for citizens to learn and use AI.

With regard to data-center buildouts, another silver lining is that, with the rise of generative AI, data gravity has decreased because compute processing costs are much greater than transmission costs, meaning it’s more feasible to place data centers anywhere in the world rather than only in close proximity to end-users. Even though many places do not have enough trained technicians to build and operate data centers, I expect tariffs will encourage data centers to be built around the world, creating more job opportunities globally.

Finally, tariffs will create increased pressure for domestic manufacturing, which might create very mild tailwinds for robotics and industrial automation. As U.S. Vice President J.D. Vance pointed out in 2017, the U.S. should focus on automation (and education) rather than on tariffs. But the U.S. does not have the personnel — or know-how, or supply chain — to manufacture many of the goods that it currently counts on allies to make. Robotics can be helpful for addressing a small part of this large set of challenges. Generative AI’s rate of progress in robotics is also significantly slower than in processing text, visual data, audio, and reasoning. So while the tariffs could create tailwinds for AI-enabled robotics, I expect this effect to be small.

My 4-year-old son had been complaining for a couple of weeks that his shoes were a tight fit — he was proud that he’s growing! So last Sunday, we went shoe shopping. His new shoes cost $25, and while checking out, I paused and reflected on how lucky I am to be able to afford them. But I also thought about the many families living paycheck-to-paycheck, and for whom tariffs leading to shoes at $40 a pair would mean they let their kids wear ill-fitting shoes longer. I also thought about people I’ve met in clothing manufacturing plants in Asia and Latin America, for whom reduced demand would mean less work and less money to take home to their own kids.

I don’t know what will happen next with the U.S. tariffs, and plenty of international trade will happen with or without U.S. involvement. I hope we can return to a world of vibrant global trade with strong, rules-based, U.S. participation. Until then, let’s all of us in AI keep nurturing our international friendships, keep up the digital flow of ideas — including specifically open source software — and keep supporting each other. Let’s all do what we can to keep the world as connected as we are able.

Love,

Andrew

A MESSAGE FROM DEEPLEARNING.AI

Course 3 of the Data Analytics Professional Certificate is live! Learn to use Python, the most important coding language in data analytics, to analyze real-world datasets, create visualizations, run tests, and apply AI tools to debug and accelerate your code. Enroll now

News

Ordinary LLMs Implicitly Take Reasoning Steps

Even without explicit training in reasoning, large language models “think” in ways that may be more deliberate than previously understood.

What’s new: Emmanuel Ameisen and colleagues at Anthropic devised a method to study how transformers generate responses to specific prompts. They also studied Claude 3.5 Haiku’s responses to specific prompts and found that the model, which is not trained to generate chains of thought, nonetheless appeared to take reasoning steps via its neuron activations.

Key insight: A viable alternative to a fully connected layer is a cross-layer transcoder, which has two layers. The outputs of the larger first layer are sparse, which makes them interpretable “features,” or individual values that correspond to concepts. By mapping an input to highly activated features, we can identify the concepts that determine the model’s output.

How it works: The team replaced fully connected layers in Claude 3.5 Haiku with cross-layer transcoders and interpreted their features.

- The authors trained one cross-layer transcoder for each fully connected layer. Given the fully connected layer’s input, the cross-layer transcoder learned to minimize the difference between its output and the fully connected layer’s output. It also learned to minimize the number of non-zero weights.

- To interpret a transcoder’s features, they substituted it for the corresponding fully connected layer and ran selected inputs through the model. They produced visualizations of inputs that caused a feature to have a high value and looked for commonalities among those inputs. In this way, they found that certain features were associated with specific words (like “rabbit”), concepts (like large or capital city), and next-word predictions (like “say D_”, indicating that the predicted token should start with the letter D), or “say capital,” (indicating that the predicted token should be a capital city).

- For each of several prompts, such as, “The opposite of small is,” they simplified a Claude 3.5 Haiku model to examine its response. They replaced the fully connected layers with cross-layer transcoders and reduced the attention computation (based on how it activated for the prompt). The simplified model was essentially a fully connected neural network.

- They built a graph that interpreted how the replacement model produced outputs. The nodes were features, and the edges represented a high contribution of one feature to another feature in a later intermediate layer. Then they replaced the features with their corresponding interpretations. For instance, if the input prompt was, “The opposite of small is,” the graph connected the feature opposite to the feature antonym, and it connected the features antonym and small to the output feature “say large.”

- They verified causal relationships between inputs, interpretations, and outputs by replacing specific layer outputs with outputs corresponding to a different interpretation. For instance, they replaced the values that represented antonym with values that represented synonym. After this intervention, prompted with “the opposite of small is,” the model generated the synonym “little” (instead of the antonym “large”).

Results: The authors built graphs that show how Claude 3.5 Haiku computes its output over a number of selected prompts.

- A graph for the prompt, “Fact: the capital of the state containing Dallas is” showed that the model determined internally that Dallas is in Texas, and then predicted Austin from the ideas “say a capital” and “Texas.” In other words, the model took steps rather than predicting “Austin” directly. To verify this conclusion, the authors replaced the features for “Texas” with the features for “California.” The model generated “Sacramento.”

- Given a prompt that mentioned several symptoms of an illness and asked which one best clarified a potential diagnosis, the model took into account the various symptoms, produced potential diagnosis internally, considered various diagnostic criteria, and decided which one to output.

- The authors’ graphs revealed how the model, prompted to describe its chain of thought, sometimes produced misleading output. Given a simple math problem and asked for the solution and the steps taken to find it, the model computed the answer correctly, and the graph and chain of thought matched. But given a more complex problem along with the expected solution and a request to double check it, the model’s chain of thought rationalized an incorrect solution, while the graph showed that the model had backtracked from the solution rather than trying to solve the problem. Given the same problem without the expected solution, the chain of thought described using a calculator, while the graph showed that the model had simply guessed an incorrect solution.

Behind the news: Last year, Google trained models to examine individual features in Gemma 2. Before that, Anthropic used similar methods to interpret Claude 3 Sonnet’s middle layer.

Why it matters: Apparently Claude 3.5 Haiku — and presumably other large language models — spontaneously perform implicit reasoning steps without being prompted to do so. Anthropic’s method reveals not only whether a model reasons or takes a shortcut, but also what it truly does well and what it only professes to do well.

We’re thinking: The authors’ approach to examining how large language models generate output is interesting. We wonder whether even pre-transformer vanilla neural networks would appear to perform some sort of “reasoning” if we were to interpret them in a similar way.

Llama’s Mixture of Vision-Language Experts

Meta updated its popular open-weights models, claiming performance superior to closed competitors in three size classes.

What’s new: Meta released two vision-language models in the Llama 4 family (Llama 4 Scout and Llama 4 Maverick) and teased a third (Llama 4 Behemoth). All three models are based on the increasingly popular mixture-of-experts (MoE) architecture, which activates only a portion of parameters during inference for more efficient processing. Llama 4 Scout boasts the industry's biggest input context window so far — 10 million tokens! — but Meta says processing 1.4 million tokens of context requires eight Nvidia H100 GPUs, and early users on Reddit reported that its effective context began to degrade at 32,000 tokens.

- Input/output: Text, image, and video in (Llama 4 Scout up to 10 million tokens, Llama 4 Maverick up to 1 million tokens). Text out (Llama 4 Scout 120.5 tokens per second, 0.39 seconds to first token; Llama 4 Maverick 124.2 tokens per second, 0.34 seconds to first token).

- Architecture: Llama 4 Scout 109 billion parameters, 17 billion parameters activated. Llama 4 Maverick 400 billion parameters, 17 billion activated. Llama 4 Behemoth nearly 2 trillion parameters, 288 billion parameters activated.

- Features: 12 officially supported languages

- Undisclosed: Distillation details, Llama 4 Behemoth details including release date

- Availability: Weights free to download under a license that allows noncommercial uses and limits commercial uses to businesses with fewer than 700 million monthly users under Meta’s terms of use

- API price: Llama 4 Scout $0.15/$0.50 per 1 million tokens input/output. Llama 4 Maverick $0.22/$0.85 per 1 million tokens input/output.

How it works: The team pretrained Llama 4 models on images and text in over 200 languages from publicly available and licensed data, including data from publicly shared posts on Facebook and Instagram. They trained Llama 4 Scout on 40 trillion tokens and Llama 4 Maverick on 22 trillion tokens.

- The team removed the 50 percent of training examples that are easiest to predict (as judged by unnamed Llama models). For Llama 4 Behemoth, they removed 95 percent of an unspecified data set.

- They fine-tuned the models using supervised learning, then reinforcement learning, then direct preference optimization.

- Llama 4 Maverick was “co-distilled” on outputs from Llama 4 Behemoth. The other teachers undisclosed.

Results: In tests performed by Meta, Llama 4 models showed strong performance relative to competing models — mostly not mixtures of experts, but some that are known to have higher parameter counts relative to Llama 4 models’ active parameters.

- Llama 4 Scout outperformed Google Gemma 3 27B, Mistral 3.1 24B, and Gemini 2.0 Flash-Lite on most of seven benchmarks that test vision (MMMU, Chart QA), coding (LiveCodeBench), and knowledge and reasoning tasks (MMLU Pro, GPQA Diamond).

- Llama 4 Maverick outperformed OpenAI GPT-4o and Google Gemini 2.0 Flash across the same benchmarks.

- On multiple benchmarks including tests of mathematics, coding, domain knowledge, and multimedia reasoning, an early version of Llama 4 Behemoth outperformed OpenAI GPT-4.5, Anthropic Claude 3.7 Sonnet, and Google Gemini 2.0 Pro but fell behind OpenAI o1, DeepSeek-R1, and Google Gemini 2.5 Pro. (The parameter counts of these models are undisclosed except DeepSeek-R1, a MoE model with 671 billion parameters, 37 billion of which are active at any given time.)

Yes, but: An experimental version of Llama 4 Maverick reached second place in Chatbot Arena behind Gemini 2.5 Pro. However, it was a variation optimized for conversation, not the currently available version. AI researchers accused Meta of attempting to manipulate the leaderboard.

Why it matters: Although the version of Llama 4 Maverick that nearly topped the Chatbot Arena is not the released version, its accomplishment says a lot about the growing power of open weights. Open models are quickly reaching parity with closed competitors — a boon to developers, businesses, and society at large.

We’re thinking: According to Meta, Behemoth beats GPT-4.5, Claude Sonnet 3.7, and Gemini 2.0 Pro, topping all but the best reasoning models — but it isn’t available yet. Something to look forward to!

Better Multimodal Performance With Open Weights

Alibaba’s latest open-weights system raises the bar for multimodal tasks in a relatively small model.

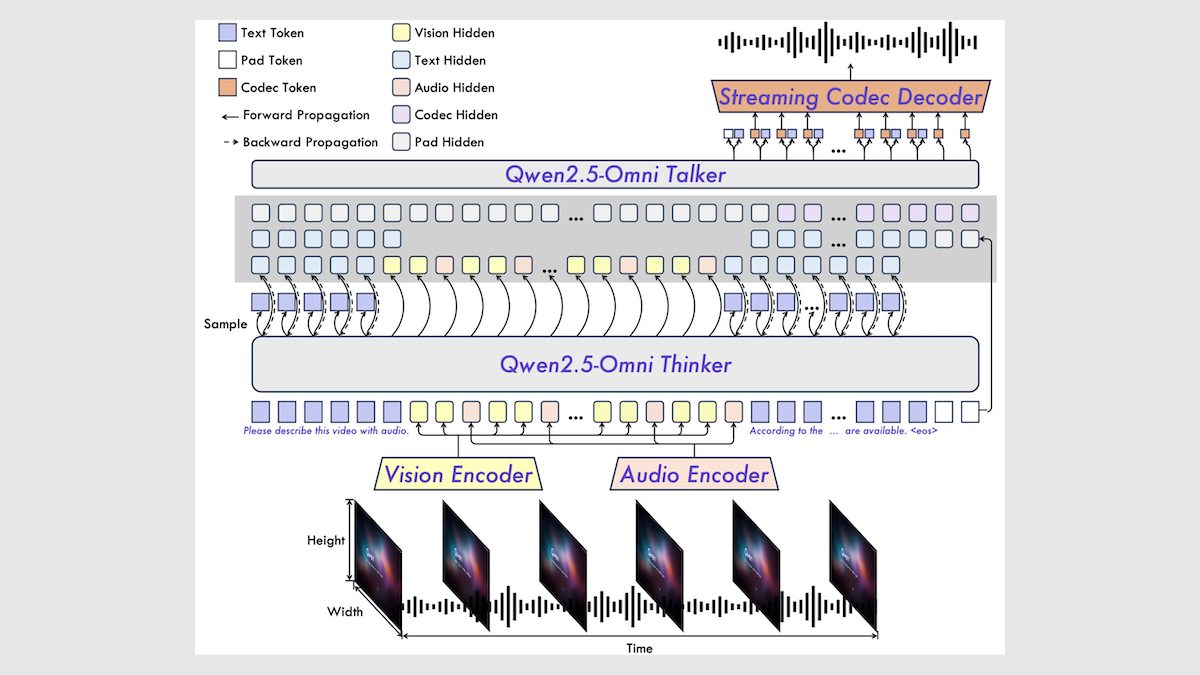

What’s new: Alibaba released Qwen2.5-Omni 7B.

- Input/output: Input: text, images (up to 10 MB per file), audio (up to 10 MB and 3 minutes per file), video (up to 150 MB and 40 seconds per file) for a total of up to 32,768 tokens. Output: text, speech

- Performance: State of the art in some audio- and image-to-text benchmarks

- Training data: 18 trillion tokens of text (identical to Qwen2.5), 800 billion tokens of images and videos, 300 billion tokens of audio, 100 billion tokens of video with audio

- Undisclosed: Knowledge cutoff, output size, adapter architecture

- Availability: Weights free to download under the Apache 2.0 license.

- API price: Input: 0.4 Yuan per million tokens of text, 25 Yuan per million tokens of audio, 1.5 Yuan per million tokens of images/video. Output: 1.6 Yuan per million tokens of text with text-only input; 4.5 Yuan per million tokens of text with audio, video, or image input; 50 Yuan per million tokens of audio with any input.

How it works: Qwen2.5-Omni 7B comprises a pretrained text transformer (Qwen 2.5 7B), pretrained vision encoder (Qwen2.5-VL), pretrained audio encoder (Whisper-large-v3), speech transformer, and audio decoder (a transformer plus BigVGAN), along with corresponding adapters of undisclosed architecture.

- The team pretrained the system in three stages. First, they pretrained the vision and audio encoders and their adapters with the frozen text transformer to generate the next text token in audio-text and image-text data. In the second stage, they pretrained the entire system to generate the next text or audio token in 1.2 trillion tokens of multimodal data. In the last stage, they pretrained the system on longer multimodal inputs.

- They fine-tuned the text transformer to generate the next token in a dataset of multimodal instruction-following tasks.

- They fine-tuned the speech transformer in three stages. First they fine-tuned the model to generate the next speech token in multimodal dialogues. Then they fine-tuned it to prefer generating speech with fewer erroneous words or unnecessary pauses via Direct Preference Optimization. Finally, they fine-tuned it to reproduce the sounds of a few particular human voices.

- At inference, given images, audio, video, and/or a text input, the vision encoder embeds video frames/images and the audio encoder embeds audio (including video soundtracks). The adapters transform the embedded frames/images and audio for further processing. From the text and embedded frames and audio, the text transformer generates the next text token plus high-level embeddings of input text, images, video, and audio. From the generated text and high-level embeddings, the speech transformer generates the next speech tokens. Finally, the audio decoder turns speech tokens into audio.

Results: The authors compared Qwen2.5-Omni 7B to similarly sized models. It performed especially well on audio-to-text, image-to-text, and video-to-text tasks. However, it performed less well on text-to-text and text-to-speech tasks.

- Qwen2.5-Omni 7B achieved state-of-the-art measures on most of the audio-to-text benchmarks tested. For example, when transcribing recorded English speech in Common Voice 15, Qwen2.5-Omni 7B (7.6 percent word error rate) beat the next-best model MinMo (7.9 percent word error rate).

- Qwen2.5-Omni 7B achieved state-of-the-art performance on some image-to-text tasks including MMstar, where it tied with MiniCPM-V (64 percent accuracy) and beat GPT-4o-mini (54.8 percent accuracy).

- In 10 text-to-text benchmarks, Qwen2.5-Omni 7B underperformed Qwen 2.5-7B but generally was comparable with Qwen2-7B, Llama 3.1-8B, and Gemma2-9B.

- On the English subset of Seed, in which the system renders text in a particular speaker’s voice based on a snippet of reference audio, Qwen2.5-Omni 7B (2.33 percent word error rate) underperformed F5-TTS (1.83 percent word error rate).

Behind the news: Multimodal systems with open weights are multiplying. For instance, AnyGPT (open weights, training, and inference code) accepts and generates speech, text, images, and music. Similarly, Mini-Omni2 (open weights and inference code) accepts and generates text, speech, and images.

Why it matters: Multimodal models typically show steep degradation on measurements of instruction-following when shifting from voice to text, but Qwen2.5-Omni does not. As the world moves toward voice-to-voice interactions, open systems that deliver performance comparable to that of closed competitors accelerate progress towards better conversations.

We’re thinking: The Qwen team is on fire! Alibaba’s steady stream of highly capable open-weights models is a gift to AI developers.

Better Than Trees for Tabular Data

If you have a collection of variables that represent, say, a cancer patient and you want to classify the patient’s illness as likely cancer or not, algorithms based on decision trees, such as gradient-boosted trees, typically perform better than neural networks. A transformer tailored to tabular data could change this situation.

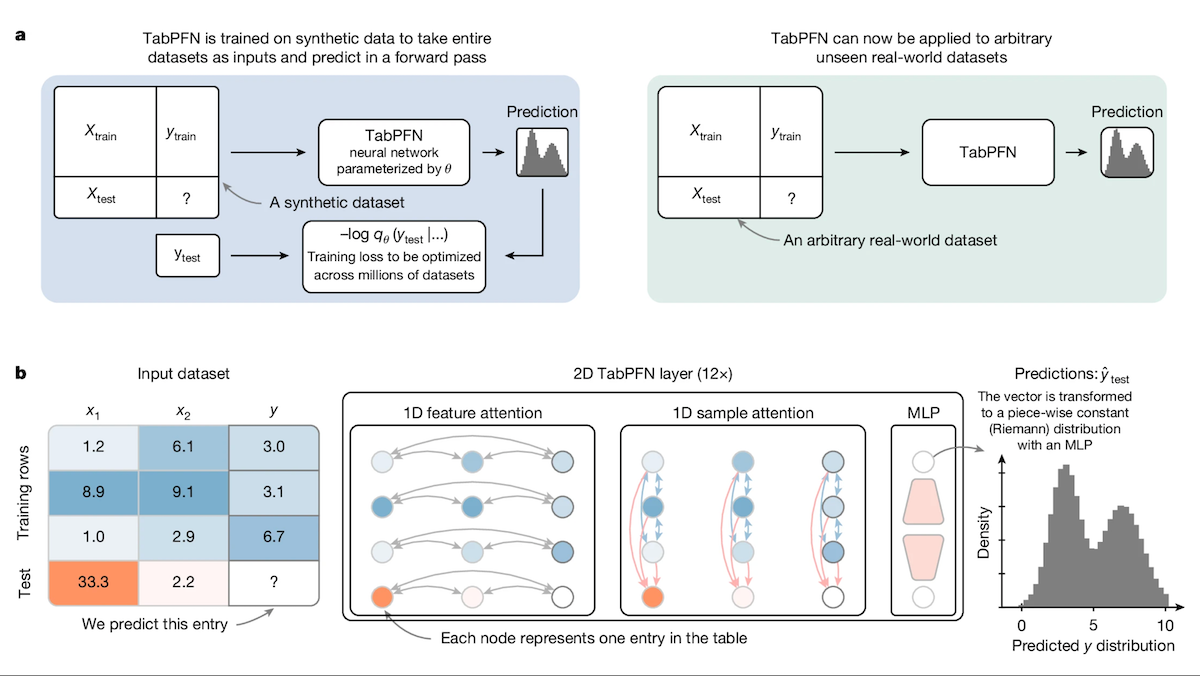

What’s new: Noah Hollmann, Samuel Müller, and colleagues at University of Freiburg, Berlin Institute of Health, Prior Labs, and ELLIS Institute introduced Tabular Prior-data Fitted Network (TabPFN), a transformer that, given a tabular dataset, beats established decision-tree methods on classification and regression tasks. You can download the code and weights under a license based on Apache 2.0 that allows noncommercial and commercial uses.

Key insight: In a typical supervised learning process, a model given one example at a time learns to recognize patterns in a dataset. If each example is an entire dataset, it learns to recognize patterns across all those datasets. Trained in this way on enough datasets, it can generalize to new ones. Applying this idea to tabular data, a transformer — unlike a decision tree — can learn to perform classification and regression on any dataset without further training; that is, without further updating the model weights.

How it works: The authors generated 100 million datasets and used them to pretrain two small transformers (around 7 million and 11 million parameters respectively) to perform classification or regression. Given a dataset of rows (say, patient data labeled diagnoses or real-estate data labeled with prices) and one final row that’s unlabeled, the models learned to generate the missing label or value. Each dataset consisted of up to 2,048 rows (examples) and up to 160 columns (features).

- To generate a dataset, the authors sampled hyperparameters, such as the number of rows and columns, and produced a graph in which each node is a potential column, and each edge describes how one column is related to another mathematically. They sampled the mathematical relationships randomly; for example, one column might be the sum of a second column with the sine of a third. They selected a subset of nodes at random, creating columns, and propagated random noise through them to fill the columns with values. To simulate real-world imperfections, they removed some values and added noise at random.

- The authors modified the transformer’s attention mechanism. Where a typical transformer block contains an attention layer and a fully connected layer, the authors included a feature attention layer (in which each cell attended to other cells in its column), an example attention layer (in which each cell attended to other cells in its row), and a fully connected layer.

- The authors trained the model to estimate the missing label in each synthetic dataset. At inference, given a dataset (with labels) and an unlabeled example, the model predicted the label.

Results: The authors tested the system on 29 classification datasets and 28 regression datasets from the AutoML benchmark and OpenML-CTR23. Each dataset contained up to 10,000 rows, 500 columns, and 10 classes. They compared TabPFN to the popular gradient-boosted tree approaches CatBoost, LightGBM, and XGBoost.

- To evaluate classification, the authors measured area under the curve (AUC, higher is better) and normalized the resulting scores across the datasets to range from 0 (worst) to 1 (best). TabPFN performed best across the datasets tested, achieving an average 0.939 normalized AUC, while the best contender, CatBoost, achieved an average 0.752 normalized AUC.

- To evaluate regression, the authors measured root mean squared error (RMSE). They normalized the resulting scores to range from 0 (worst) to 1 (best). TabPFN achieved 0.923 normalized RMSE, while the next-best method, Catboost, achieved 0.872 normalized RMSE.

Yes, but: The authors’ method is slower than decision tree methods with respect to inference. To process a 10,000-row dataset, TabPFN required 0.2 seconds while CatBoost took 0.0002 seconds.

Why it matters: Transformers trained on large datasets of text or images can perform tasks they weren’t specifically trained for and generalize to novel datasets when performing tasks they were trained for. But when it comes to tabular data, they haven’t been competitive with decision trees. This work bridges the gap, unlocking a wide variety of new use cases for transformers. Not only does it process tabular data as well as popular tree-based methods, it doesn’t require additional training to process novel datasets.

We’re thinking: Decision trees date back to Aristotle and remain extremely useful. But a transformer-based approach could open the processing of tabular data to benefit from the ongoing innovation in transformers.